Look out for Sherlock Holmes, he is on the Most Wanted list

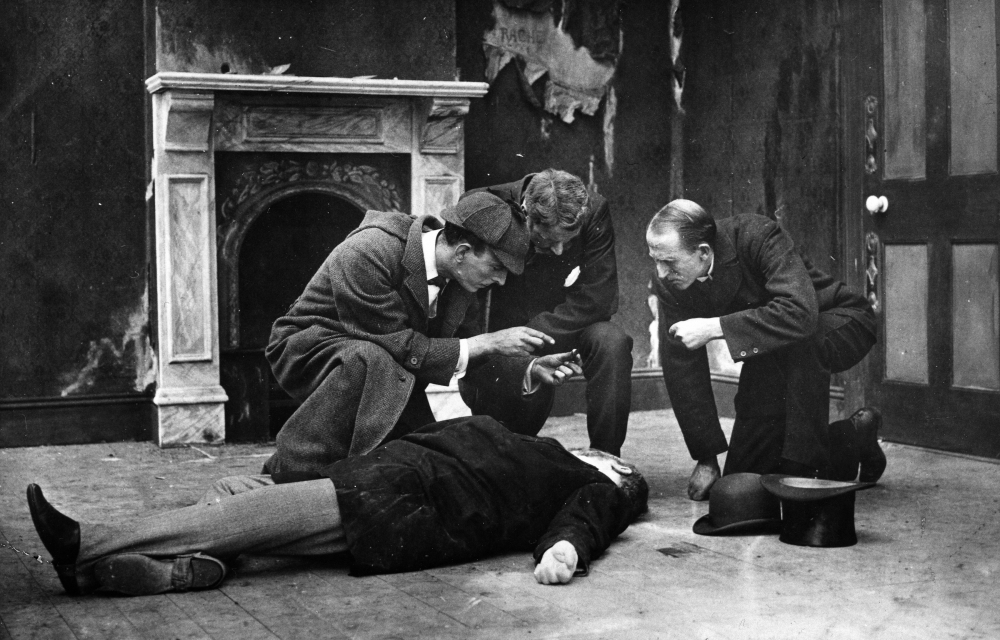

Cheer up, Sherlock. You’ll crack the case. James Bragington as Sherlock in the missing 1914 film

The FBI’s Most Wanted list: a collection of murderers, violent robbers, organised crime lords etc. Sherlock Holmes would have loved it.

In moments of boredom, or simply when the equinoctial gales were blowing hard, he might peruse the list for international criminal masterminds and remind Watson how he had at one time apprehended this one, outwitted that one and warn that another could be on his way to London.

But sadly, Sherlock had no such list. What he does have is pride of place on another Most Wanted list – the British Film Institute’s Most Wanted. No, Sherlock wouldn’t have been quite so interested in that list. Still, it’s all we’ve got.

Now take a seat Watson. I will explain everything and then perhaps you will be kind enough to furnish me with your opinion on the case (via the comments form).

Once upon a time, back in the digital stone age – aka the 20th Century – when films were actually on film, there was often only one proper copy and as saying goes, when it’s gone it’s gone.

It’s hard to think of a film just disappearing today. In our digital era where making a copy of a media file is as easy as dragging it onto a hard drive there are practically more versions on your average illegal file sharing site than there are humans to view them. In short, there isn’t much chance of a film disappearing forever.

Meanwhile, a few years ago over at the British Film Institute someone – more probably some committee – decided that it would be good to jot down a list of classic British movies that had disappeared without a trace.

A noble cause – but what to call it? Everything has to be media catchy these days, for without the oxygen of publicity the plan would surely fail.

BFI Marketing Genius: Ok, so you want us to publicise your missing films list. Fine, but we’ll need a name for it.

BFI Archive Geek: Why?

BFI Marketing Genius: It needs a brand. Everything needs a brand.

BFI Archive Geek: Oh right. How about: “BFI’s missing movies list?”

BFI Marketing Genius: Boring.

BFI Archive Geek: “BFI’s cinema classics that are gone but we’re hoping to find one day.”

BFI Marketing Genius: Yawn.

BFI Archive Geek: How about The “BFI’s Most Wanted!” Get it? It’s like the FBI but we’ll swap the F and the B.

BFI Marketing Genius: That was what I was thinking. I’ll tell them I’ve come up with the perfect name.

And so it was that in 2010 the BFI’s Most Wanted list was released, containing 75 films that they were desperately seeking. As it turned out, they weren’t all technically missing. In fact in the aftermath of the press release several people emailed in with the shock news that far from being missing, they had a copy of the DVD on their shelf. A little cringe-making for the list’s curator but hold on – for the BFI just having a copy of it doesn’t mean it’s necessarily preserved. As they defiantly announced:

“While it’s great to know that a film has survived on tape or DVD, this doesn’t mean it’s out of danger. Many such bootleg copies derive from television screenings here or abroad; the film will have been transmitted from a tape format, meaning the film material it originally came from could be long gone.”

Overall though, the campaign was pretty successful, they dug up loads of movies from the 20s to the 80s, not always exactly the versions they were looking for but generally proving the concept that if you ask enough film buffs to look in the shoe boxes in their attics you’re going to find some interesting material.

Four years later and long overdue the list makers have finally focused on the perplexing case of the missing 1914 film of A Study in Scarlet. This silent film, directed by George Pearson, was made for the Samuelson Manufacturing Company. I know, that doesn’t sound much like a movie studio, but then again it was 1914.

Apparently they had great difficulty casting Sherlock. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was still alive and the British public had firm ideas about the mannerisms and general appearance of the protagonist thanks to the popular original drawings by Sidney Paget.

This was a time before central casting, or possibly even professional casting agents, but luckily there was a chap working at Samuelson Manufacturing Company who looked a bit like Sherlock Holmes, so he got the gig.

James Bragington was therefore found himself as one the earliest movie Sherlocks. It is unclear as to how good his performance was, and Bragington has no other known credits. According to the director however, he played the part “excellently”. It would be very nice to be able to make our own critical assessment of the actor and the movie itself but annoyingly, as I have just mentioned, it’s missing.

A scene from the lost film version of A Study in Scarlet

As for clues we don’t have a lot to go on. We know that it was shot in summer 1914 at Worton Hall studios and on location at Cheddar Gorge in Somerset and Southport Sands in Merseyside, where the fine scenery stood in for the Rocky Mountains and the Utah plains.

The BFI reckons there must be a copy somewhere, although if there is, who knows what condition it’s in? Either way, a moth eaten movie is better than no movie, so anyone who has even the most preposterous Holmesian hunch as to where it may be is implored to contact the British Film Institute on Twitter using the hashtag #findSherlock or by emailing sherlockholmes (at) bfi.org.uk

It’s a long shot but then again, most of Sherlock’s theories are and they usually pan out, so let’s have faith, and perhaps a little look in your Liverpudlian movie mogul great-great uncle’s shoe boxes.